Serious anonymity and the presence of knowledge, never nonsense; a tremendous amount of being useful to others by responding to them; and being able to feel the satisfaction of our useful presence”

Alejandro de la Sota

Keys

To understand

modern Spanish

architecture-

Alejandro de la Sota

After the end of the Spanish Civil War in 1939, the divided country was plunged into a severe crisis. In addition to the difficulties of rebuilding a nation almost from scratch, Spain was suffering from a lack of economic resources and serious cultural isolation. This was the situation when the pioneering Spanish modern architects began working professionally, because although modern architecture had emerged at the end of the 1920s, it had been paralysed during the war.

Despite the lack of resources, these architects made use of other skills not taught in universities. Thanks to their enthusiasm, sense of responsibility and commitment to their craft, they managed to leave their mark on history by writing one of the most brilliant chapters in Spanish architecture.

This generation of architects took on ethical, aesthetic and social leadership at a time of crisis and scarcity and this was reflected in their writings, interviews and lectures.

Conceptual clarity, technical rationality based on economy with resources, ecology based on respect for Nature, and common sense, practicality and functional optimisation, were some of the values contributed by the architecture they created. Their modern discourse, adapted to the collective and cultural situation in Spain, had a common denominator: architecture seen as a useful and necessary service for society.

Alejandro de la Sota

The pioneering modern architects were convinced that architecture, as the container for all our activities, has a direct impact on people's well-being. It should not merely serve as shelter, it should also improve our lives.

Alejandro de la Sota

For them, it was essential to create environments where users would feel good. And this final objective could only be achieved if concepts such as the clarity of spatial order, human scale, light, the user’s interaction with nature and the qualities different materials could generate were understood in the thinking process.

The environments created by the architecture had to be comfortable and comforting; generate feelings of harmony, peace and quiet; and, in addition, promote values:

Their proposals were based on a deep understanding of the physical and human environment in which they were developing. They listened to what the place had to tell them, while always remaining contemporary.

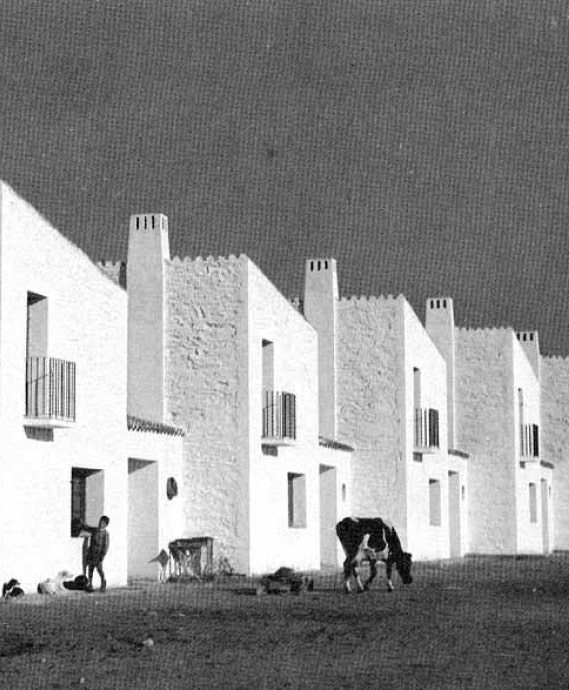

They took popular architecture as a reference because they could use it to resolve living needs naturally and directly with an efficient use of the environmental resources and materials offered by their surroundings. It also offers simple solutions, based on common sense, economy and constructive rationality. But, rather than try to imitate its forms, they wanted to assimilate and reinterpret its essential elements and resources in response to the climate, adapted to the needs and technical resources of the time. To do this, they worked from abstraction and the use of new materials. This allowed them to integrate the architecture into the landscape and create a link with the memory of the place, involving the residents in its culture and customs.

They intended to integrate their proposals into the natural environment to make it more beautiful, naturally and discreetly. But they saw the landscape was not as an element to be contemplated from afar. It was a living space, where residents would be in close, direct contact with Nature. The use of intermediate spaces where indoors and outdoors merge into a single element and the use of large glass windows allowed them to introduce the landscape into this new architecture.

The cultural references for this generation of architects were very broad. They had a great cultural and artistic background and, in certain works, they took the liberty of designing their proposals as a whole package, delivering their clients rich works full of all kinds of unique elements or working in cooperation with other artists of the time.

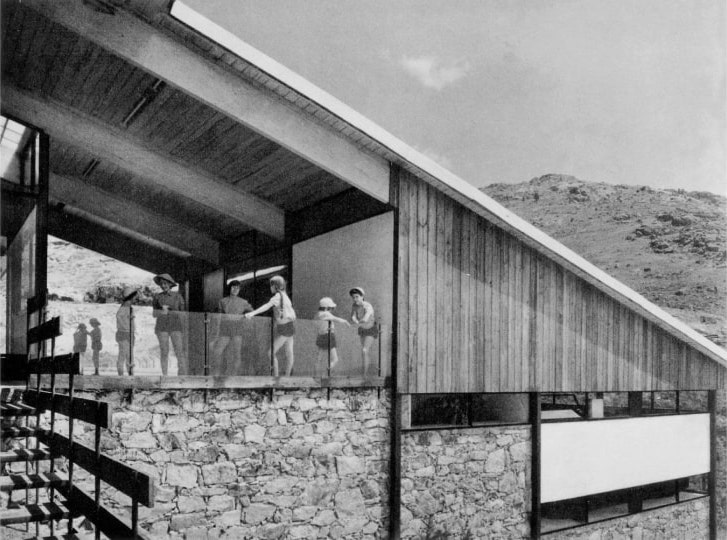

They understood their creations as complete works, starting from the general and defining each component part. For this reason, in many works designed during this period, we can see the architect's thinking affecting the work at all levels, including objects, the design of fittings and furniture, and other elements making up the space and forming an inseparable part of the work.

Alejandro de la Sota

This group of architects tried to use the minimum technical resources with the most efficient materials available to achieve the goals they set themselves. They did so precisely, without concessions to anything superfluous. Once the materials had been chosen, their architecture was developed based on the logic of the construction technique used. They used the constructive elements in a natural way, with honesty and sensitivity.

Innovation was never forgotten. The architects were so committed to the result that they investigated the potential of their materials and suggested new applications or technical improvements. They worked with engineers and technical professionals, forming multidisciplinary teams to jointly promote technological development that would have been absolutely unimaginable just a few years earlier.

“Thinking is always a tremendous endeavour. It is much more comfortable to simply believe blindly what others have developed than to do research or test out things on our own. On the contrary, I believe that for science to really move closer to art, it is necessary to assume that any problem

forces the invention of a response and that any specific question, rationally and rigorously analysed, leads to the need to create or invent, even if laws and rules have to be broken in the process”

Félix Candela.

Alejandro de la Sota

The modern architecture designed by the pioneers rejected form as an external image: the constructed idea was a result of posing a series of initial problems that were resolved by providing solutions to specific needs. Their proposals used abstraction as a tool to seek the essence of the idea, giving it form in the final construction.

This formal sincerity, or coherence of design, where the external result is the expression of an internal order, made their buildings timeless.

The pioneering architects of the Spanish Modern style were convinced that architecture should improve people's welfare. What were the key factors that made this period one of the most brilliant in Spanish architecture?

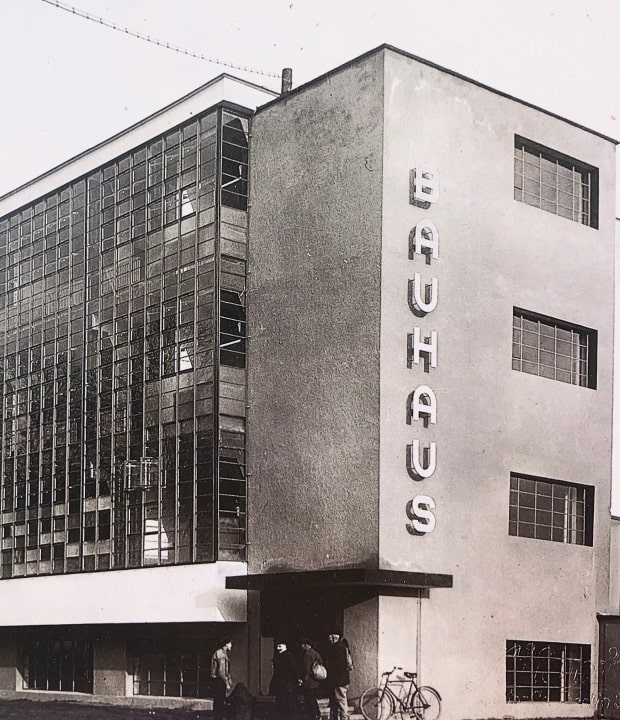

Bauhaus School, Walter Gropius, Dessau, 1932.

The leading figures in Modern Architecture on the international scene were Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius and Mies van der Rohe.

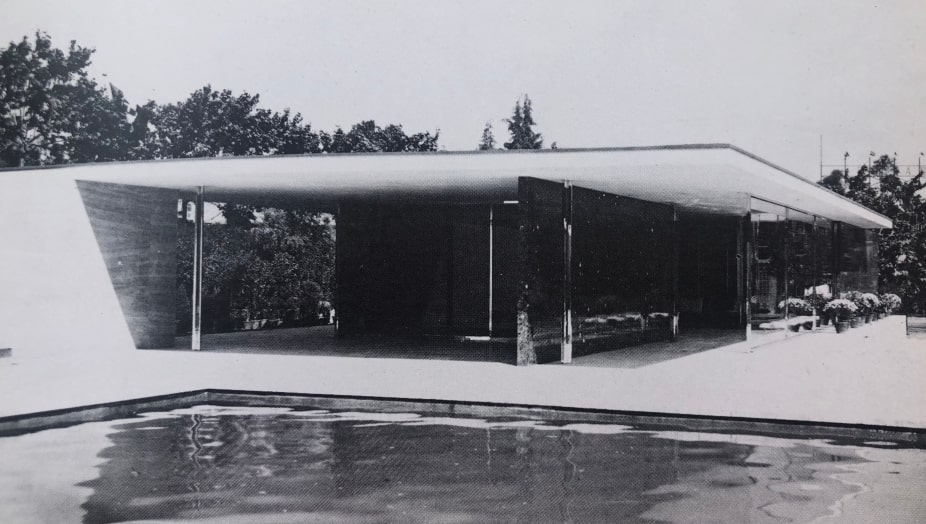

However, the spread of international modern architecture in Spain began in the late 1920s and early 1930s. The German Pavilion by Mies van der Rohe, built for the 1929 Barcelona International Exposition, shows us how far away the historicist, monumental architecture being produced in Spain under the Primo de Rivera dictatorship was from avant-garde architecture in Europe.

A year later, a group of architects founded GATEPAC (the Group of Spanish Artists and Technicians for the Progress of Contemporary Architecture), as the Spanish division of the ICMA (International Congress of Modern Architecture). Its main representatives included Josep Lluís Sert, Antonio Bonet, Josep Torres Clavé, Fernando García Mercadal and José Manuel Aizpurúa. Through their publication AC Documentos de Actividad Contemporánea, they spread their modern ideals and the work of the great European masters, such as Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, Gropius, Breuer and Neutra. In this way, some of the leading buildings being constructed on the international scene began to be introduced in this country.

Coexisting with them were other architects also involved in the renewal of styles who developed a kind of 'modern architecture' with expressionist rationalism. These included Bergamín, Blanco Soler, Secundino Zuazo and L. Gutiérrez Soto.

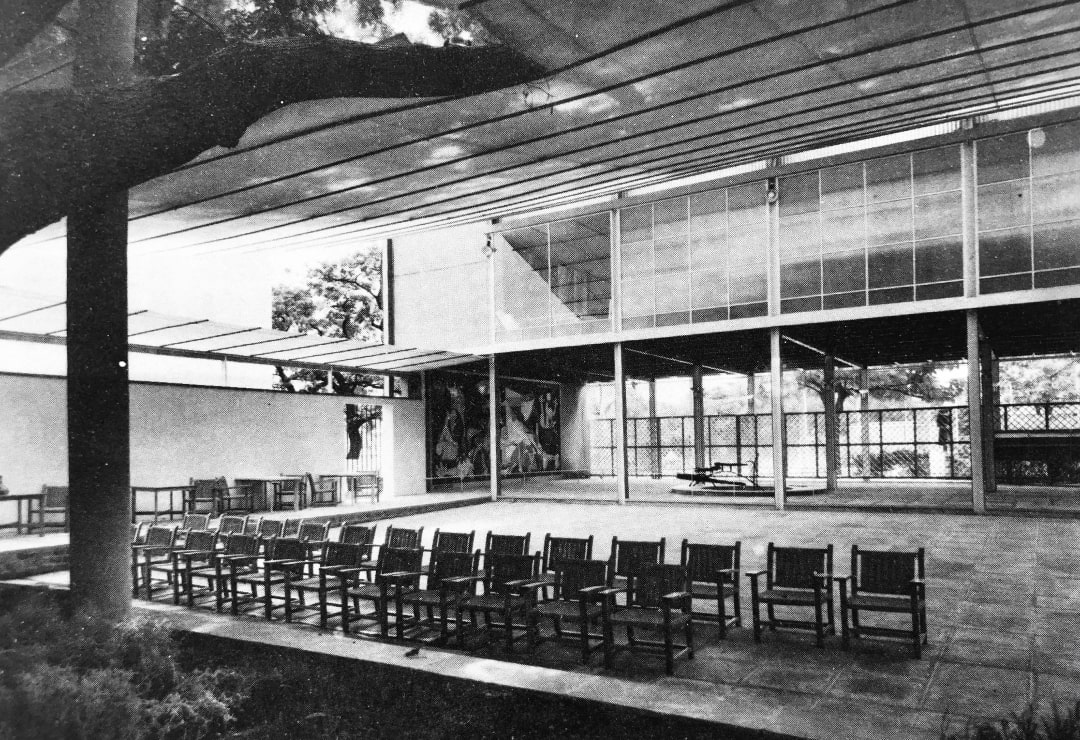

Spanish Pavilion at the Paris International Exhibition in 1937, Josep Lluis Sert.

In 1934, a group of architects and engineers, including José María Aguirre, Modesto López Otero and Eduardo Torroja, founded the Eduardo Torroja Institute, devoted to research in the field of construction, materials, industrialisation and technical rationalism.

But in 1936 came the Civil War. This brought about a tremendous upheaval in all areas, including architecture, and the incipient modern movement was paralysed. The GATEPAC, associated with Republican ideology, was dissolved following the exile or death of many of its members. Its contributions were censored, as they were considered to be opposed to the religious and nationalist ideals upheld by Franco's regime, and they were forgotten.

Residential building, Francisco de Asís Cabrero, Madrid, 1947.

Photograph: Kindel Archive.

At the end of the Spanish Civil War (1939) the country was completely divided. The architects who remained in Spain directed their activity towards a historicist, monumental national architecture, serving the new regime. The imperialist style that was developing in Germany and Italy, completely alien to international trends, served as an influence during this period.

The generation of young architects who graduated in the 1940s, including Miguel Fisac, Josep María Sostres, José Antonio Coderch, Alejandro de la Sota, Rafael Aburto, Francisco de Asís Cabrero, José Luis Fernández del Amo and Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza, began working professionally in the context of economic hardship and cultural isolation during the post-war period.

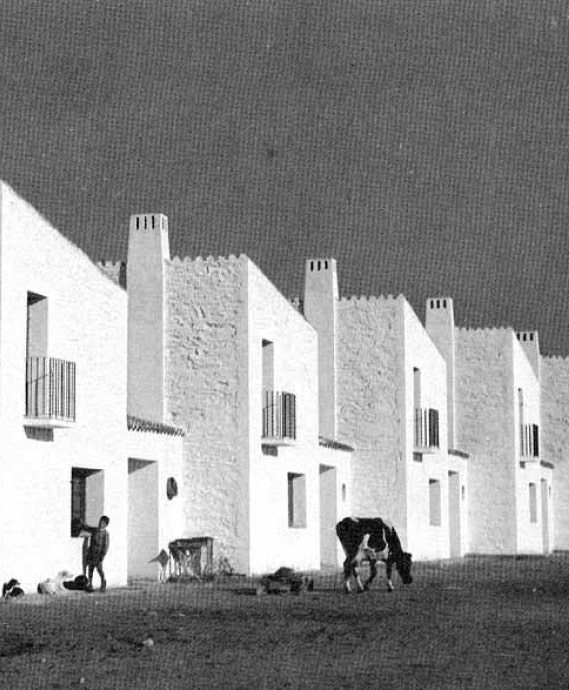

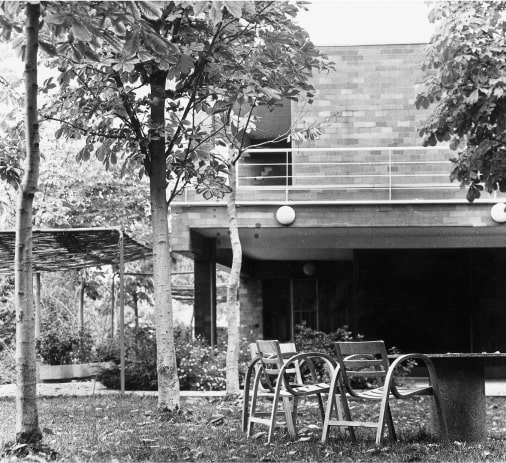

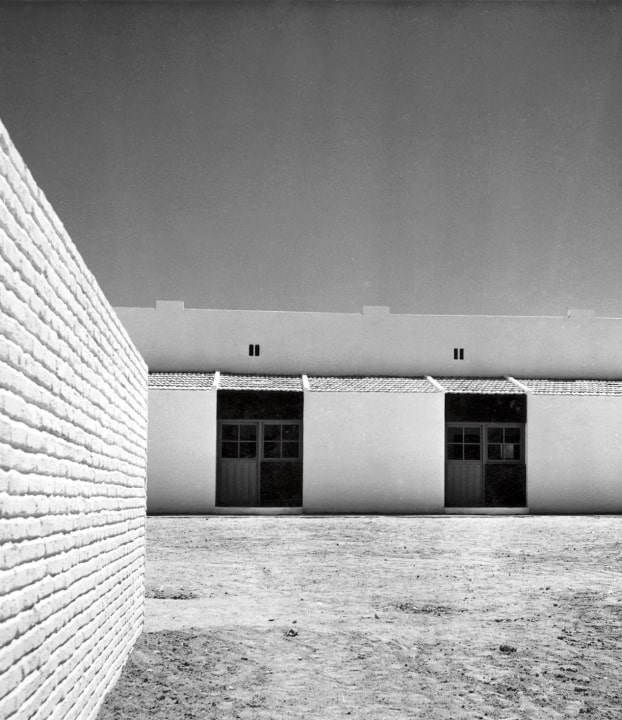

Biological Mission. Alejandro de la Sota. Salcedo (Pontevedra), 1949.

Learn more about this projectDuring these years, the political climate of the country, the academic training they received and the scarcity of resources led them to develop a historicist or traditional architecture. Their main conceptual reference at the time was popular architecture, with ethical qualities based on technical honesty, the absence of superfluous elements and integration with the environment – concepts also present in the Modern movement.

Alejandro de la Sota

Some members of the generation of young architects began to work planning rural settlements for the National Settlement Institute, an official organisation set up in 1939 to reactivate the agrarian economy. It continued to operate until the 1970s, with high-quality buildings reflecting the development of architecture in Spain.

Coinciding with the end of World War II (1945) and towards the end of the forties came the first communications with the outside world. Young architects now had access to foreign magazines that arrived in Spain showing buildings by architects such as Mies van der Rohe and Frank Lloyd Wright. This had two consequences: first, they took on Modern values in an individual, intuitive and self-taught way, learning from everything new that they had not known about before. Secondly, they developed a critical stance against the historicist architecture being produced in Spain.

So, the principles of the interwar Central European Modern Architecture of the Bauhaus masters and Le Corbusier, based on rationality, universality, social commitment, functionality and formal abstraction, were assimilated. But they were enriched with new touches, such as attention to place and local tradition, or the organic relationship between form and structure typical of the American organicism of F. L. Wright or the Scandinavian empiricism of Alvar Aalto, in line with the new reinterpretations of Modern Architecture being made in different Western countries.

In 1949, José Antonio Coderch began the resurgence of truly Modern architecture in Spain with his residential building in Barceloneta, which he followed up with the Ugalde House, built two years later.

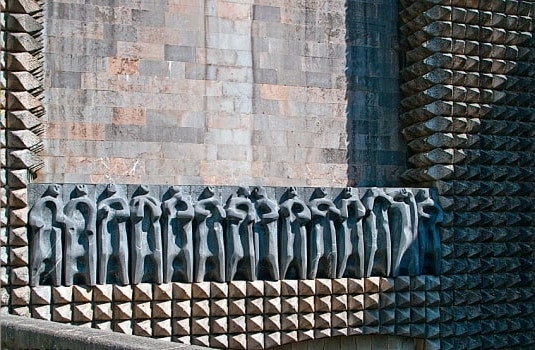

After that, the first proposals appeared in which a certain compromise between monumental academic architecture and modernity could be observed, with the influence of various foreign architectures – Scandinavian, German and Italian – operating along these lines. This was the case of the complex for the 1st Countryside Fair in Madrid (1951), by Francisco de Asís Cabrero and Jaime Ruiz; the winning design (1950) for the Basilica of Aránzazu, in Guipúzcoa, by Javier Sáenz de Oíza and Luis Laorga; and the winning proposal in the competition for the National Trade Union Office (1952) in Paseo del Prado in Madrid, by Rafael Aburto and Francisco de Asís Cabrero.

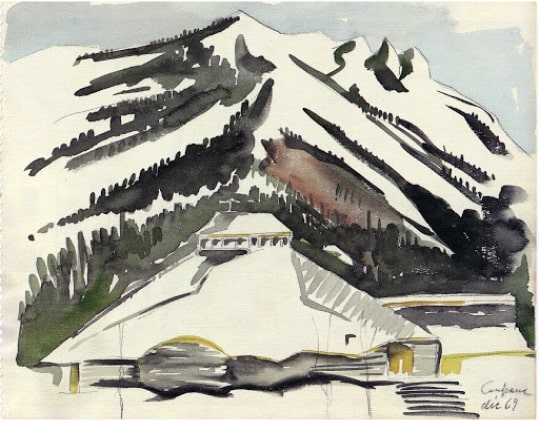

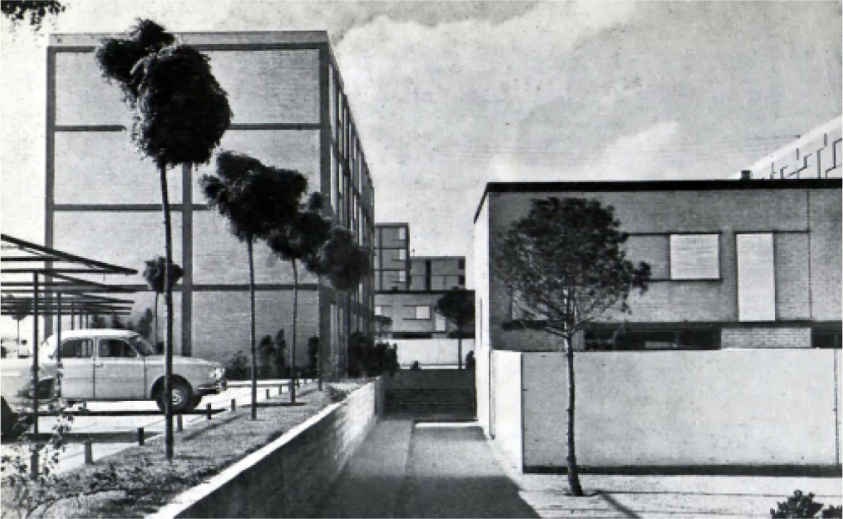

Fuencarral B overspill town, Alejandro de la Sota, Madrid, 1955.

From the 1950s onwards, when the political and cultural environment became less hostile, the architects of the new generation began to express their own poetic style. But they did it individually, due to the introspective attitude they had developed during the post-war period of isolation. In their works, Modern principles evolved and were adapted in many different ways as responses to the social and cultural situation in Spain.

During these years, plans emerged to rebuild neighbourhoods destroyed during the war. At that time, the big cities were facing a real and very serious housing problem due to population growth and the exodus from rural areas. Some young architects, committed to finding solutions for this social situation, opened forums for debate on housing and the suitability of particular types and construction methods. Assemblies and competitions were held, where Modern propositions and reconstruction models deriving from the world wars resurfaced. The new social demands had to be met by making use of the technical advances of the time. The working-class neighbourhoods built on the outskirts of Madrid to solve the housing shortage, such as the planned or overspill towns, already show a full assimilation of these values.

In 1957, some of the young architects made their first collective trip to Berlin to Visit the innovative residential buildings of the 'Interbau', built by avant-garde architects like Walter Gropius, Alvar Aalto, Oscar Niemeyer, Arne Jacobsen and Heinz Hossdorf, as well as works in Berlin by Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier. The experience deeply marked the group of architects, as it allowed them to see at first hand the suitability of the architectural premises of the Modern masters. On their return to Spain they would try to put them into practice.

Alejandro de la Sota

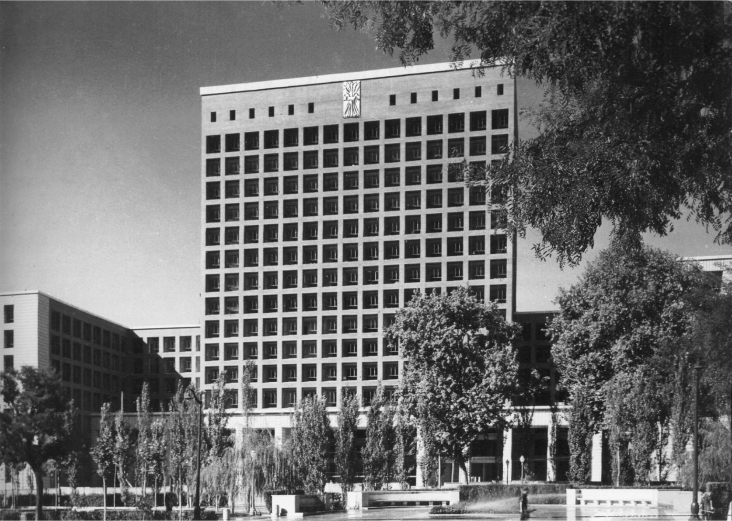

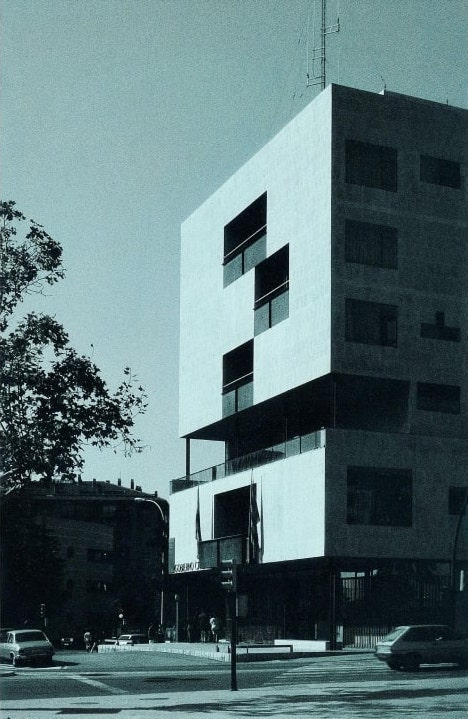

That same year, the winning projects in the competitions for various Treasury offices and, above all, the winning proposal in the competition for the Civil Government Building in Tarragona, designed by Alejandro de la Sota, reflected the modernisation of Spanish architecture, with their decidedly modern layout and official nature.

Civil Government Building in Tarragona. Alejandro de la Sota. Tarragona, 1957.

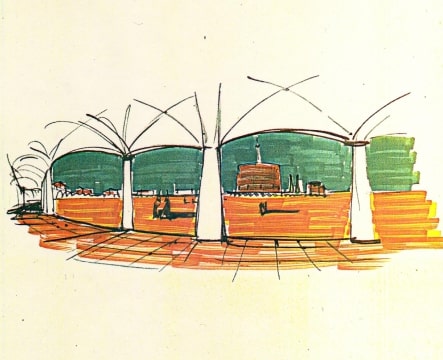

Learn more about this projectA year later, the project selected for the Spanish Pavilion at the Brussels Fair, by José Antonio Corrales and Ramón Vázquez Molezún, represents the full acceptance of Modern Architecture as the official style of the State before the international community.

Throughout the decade, some of the leading figures in the Spanish Modern movement, such as José Antonio Coderch, Jorge de Oteiza, Ramón Vázquez Molezún, José María García de Paredes, César Ortiz Echagüe, Manuel Barbero, Rafael de la Joya and Fisac, received the first international awards recognising their architectural quality.

In addition, the most important architects of the time, such as Neutra, Wright, Le Corbusier, Aalto, Gio Ponti and Sartoris, Visited Spain, giving lectures and conferences that served as a great stimulus to the new generation of architects to continue with the development of the Modern style, reinterpreting and assimilating it out of respect for Spain’s landscape and cultural values.

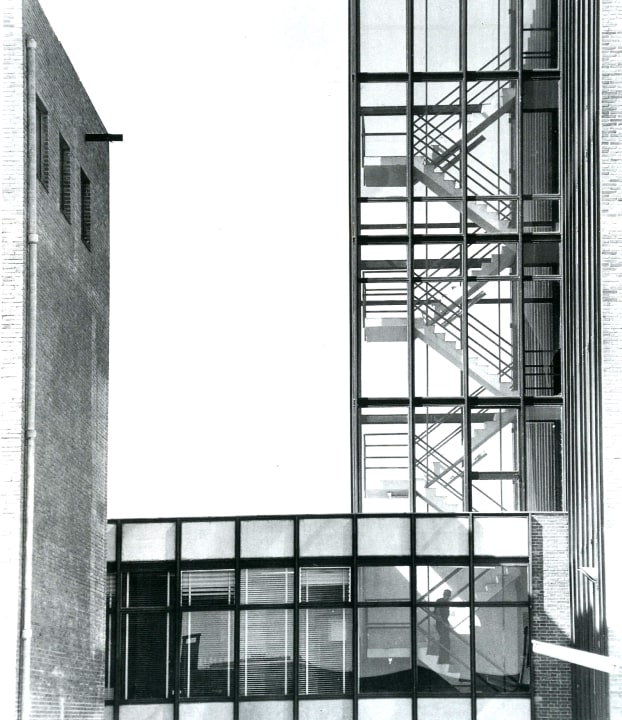

Monki Factory, Alas and Casariego, Madrid, 1962. SH FCOAM Archive.

Learn more about this projectDuring the sixties, coinciding with the years of economic recovery and industrialisation of the country, the Modern style continued booming in Spain, leaving us a wide repertoire of works of unquestionable architectural quality that remain fundamental references for architecture today.

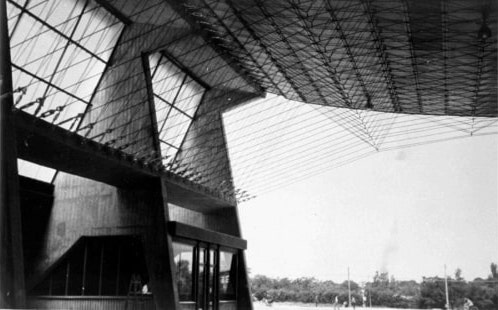

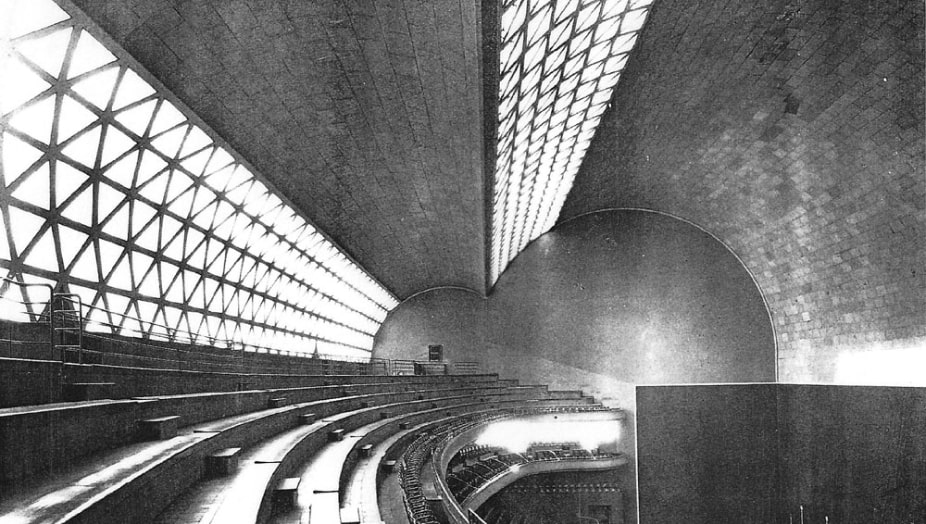

Maravillas Gymnasium, Alejandro de la Sota. Madrid, 1962.

Learn more about this project

As relations with the outside world expanded, Spanish Modern architecture began drawing on new foreign references, such as the generation of Italian architects led by Ernesto N. Rogers, who encouraged the consideration of historical values and pre-existing buildings to integrate Modern architecture into old districts; and Team X, who focused their attention on the urban environment and the essential role of architecture in shaping the collective public space.

Jorba Laboratories. Miguel Fisac. Madrid, 1965. Fisac Foundation Archive.

Learn more about this project

In a context of great optimism, some architects developed an organic line of work, with great formal freedom, taking as references the work of F. Lloyd Wright, Alvar Aalto, Eero Saarinen, Jörn Utzon and Le Corbusier himself in his more mature period. They have left us some of the iconic works of Spanish Modern architecture.

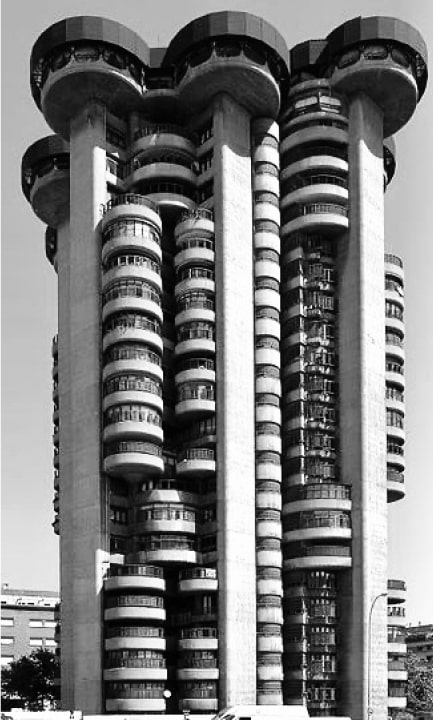

Torres Blancas building. Francisco Javier Saénz de Oíza. Madrid 1962-68.

Learn more about this project

Other architects, such as Alejandro de la Sota, Rafael Leoz and Cabrero, remained faithful to Modern principles to resolve different needs effectively, based on rationality, abstraction, essentiality, and always with the candid, precise use of the available construction technologies.

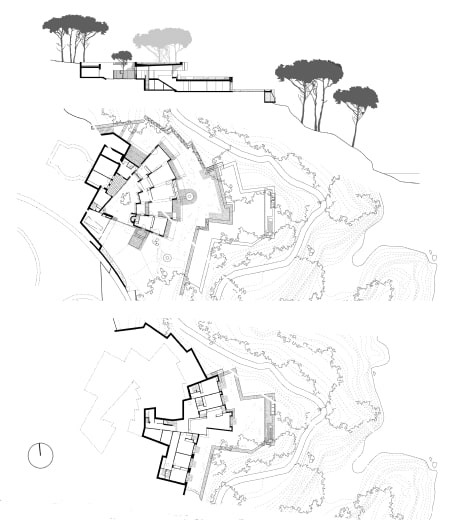

Domínguez House. Alejandro de la Sota. La Caeyra, Pontevedra, 1973-76.

Learn more about this projectIn the early 1970s, the Modern movement was embroiled in a major dilemma at international level, resulting in a crisis of values and a wide diversification of positions. In Spain, the brilliant contributions of the generation of architects that emerged in the post-war period managed to update the country’s architecture in just 20 years. Most importantly, they served as a guide, lighting the way for many architects of later generations who found in these masters the solid foundations for building the Spanish architecture of today.

The pioneering architects of the Spanish modern style took on ethical, aesthetic and social leadership with passion and enthusiasm at a time of crisis and shortages. Despite working in an era when resources were in short supply, their great enthusiasm, sense of social responsibility, commitment to architecture as a profession and innovative spirit led them to write one of the most brilliant chapters in 20th-century Spanish architecture. Their writings, interviews and lectures reflect diverse but coherent ways of experiencing and thinking about a life in architecture. Ultimately, their interpretations of the discourse of modern architecture are different, but they all have a common denominator: seeing architecture as providing a useful service to society.

The result is summarised in a set of buildings considered to be masterpieces not so much for the architect who designed

them but rather the knowledge and values they transmit. A search for rigour and technical rationality based on economical use of resources; an effort to bring architecture closer to other technical disciplines; attention to all scales (from details and furnishings to integrating buildings into the surrounding landscape to create an integral work of art); ecology based on respect for nature and common sense; and functional optimisation are among the most outstanding values in the architecture of this period.

This fruitful period has left us a huge architectural legacy which we must keep alive, with magnificent works that continue to act as a great stimulus to the current generations of architects. In the context of crisis in which we now find ourselves, affecting the economy and society as well as health and architecture, we need to consider their thinking and validity and reflect on what the foundations of the role and position of architects and architecture in our society should be today. In the words of Lluís Comerón, president of CSCAE:

“The great architects of modern Spanish architecture had a commitment to quality, excellence, society, and people […] a commitment to emotion, cultural rigour and industry; and a global commitment to the best way to build and improve our environment […] that’s the best we have in order to face our future. Now we are in a time of change, and in that change there is a great opportunity in architecture. As Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon, pointed out: “Just as important as knowing what’s changing is knowing what’s going to remain important over the next few years”

In short, it is a matter of looking backwards to gain forward momentum.

The pioneering architects of the Spanish Modern style were convinced that architecture should improve people's welfare. What were the key factors that made this period one of the most brilliant in Spanish architecture?

DOCOMOMO International is a non-profit organization dedicated to documentation and conservation of buildings, sites and neighborhoods of the Modern Movement. It was initiated in 1988 by Hubert-Jan Henket, architect and professor, and Wessel de Jonge, architect and research fellow, at the School of Architecture at the Technical University in Eindhoven, the Netherlands.

The World Monuments Fund (WMF) is an independent organisation devoted to safeguarding the most precious places in the world with the aim of enriching people's lives and fostering mutual understanding between cultures and communities. Since 1965, it has been preserving cultural heritage around the world, participating in the protection of more than 700 sites in 112 countries.

The Canadian Centre for Architecture is an international research institution based on the belief that architecture is in the public interest. It produces exhibitions and publications and sees its collection as a resource to be developed and shared, progressing with research and offering public programmes in addition to other activities related to the world of architecture.

The Mies van der Rohe Foundation was set up in 1983 by Barcelona City Council with the initial aim of carrying out the reconstruction of the German Pavilion designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich for the Barcelona International Exhibition in 1929. As well as its responsibilities for conserving and promoting knowledge of the Mies van der Rohe Pavilion, the Foundation is also concerned with contemporary architecture and urban planning, raising awareness, publicising issues and encouraging debate.

The Casa da Arquitectura de Matosinhos, created in 2007, is a non-profit cultural entity that has been asserting itself in the universe of content creation and programming for the national and international dissemination and affirmation of architecture in society. Its action involves not only architects, but also people and entities from various cultural and social fields that promote and sponsor the public interest in architecture.

Iuav Archivio Progetti was founded within the Fondazione Angelo Masieri in 1987 and since then has been actively involved in researching, acquiring, organising and publishing 20th- and 21st-century architectural archives. It is an international benchmark in organisational techniques, especially in the field of architectural archives.